There’s “fishing blind” (casting when you can’t see the fish), and then there’s “fishing blindfolded”, which is how many people might describe midge fishing.

Sub-#20 flies can be invisible on the water and seemingly impossible to detect a strike with them. But I’ve been using this simple method for many years, and it’s become my go-to strategy for fishing midge dries and emergers (or any small flies that are difficult to see).

But first, I should note this method of strike detection is meant specifically for slow, smooth water (usually larger, longer runs or pools) where you see fish actively taking midge adults on the surface or emergers just below the surface. In some cases, you’ll be able to see the fish, but often, you’ll only be able to see its rises. And this is where the technique I’m about to describe really shines.

This might sound like a niche application, but it’s actually quite a frequent situation since: a). chironomids are almost always the most abundant food source for trout resource in any watershed, b). they hatch all year round, and c). the type of runs and pools mentioned above exist on all types of streams: freestones, spring creeks, tailwaters, etc..

Plus, after the hatches of summer and fall die down, midges take over and hatch throughout the winter, so I use perimeter strike detection constantly in the “off season”.

So you can see why it’s one of the tools I rely upon most often.

Perimeter Strike Detection

The reason most people can’t see their #24 fly is precisely because they’re looking for the fly. In this method, you don’t focus on seeing the fly itself; rather, you focus on where you predict the fly to be given the water speed and distance. Let’s look at it step-by-step.

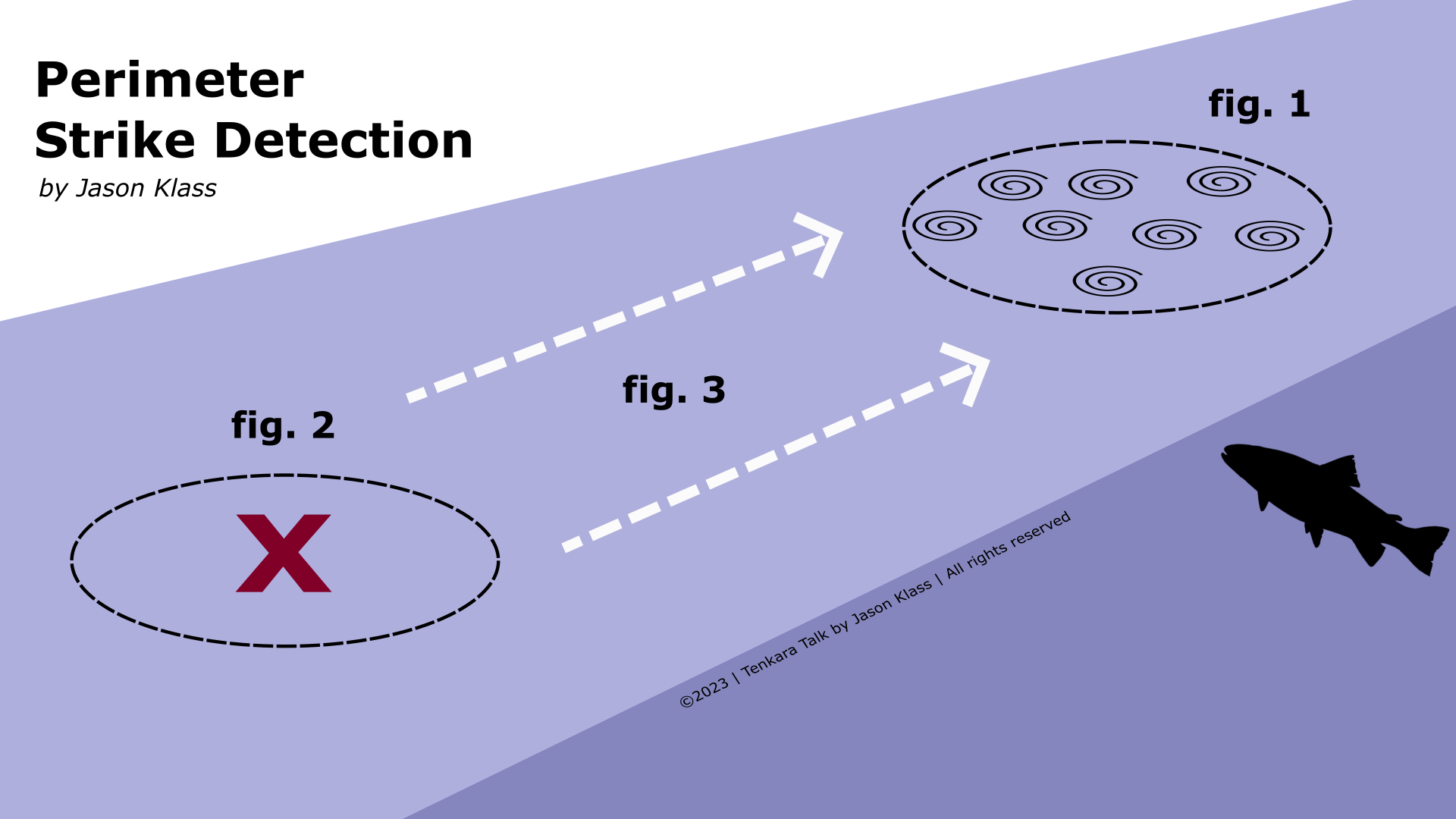

- Identify the Fish’s Rise Perimeter. If there are multiple trout rising in the run, focus on one specific one and identify its feeding pattern. When trout are on midges, they’ll normally hold near the surface, and you’ll see them rise in a particular rhythm (this can be affected by how heavy or light the hatch is, but it’s nonetheless predictable). The rises won’t be in exactly the same place every time, but will be within a certain “perimeter” the trout feels comfortable rising within–a predictable pattern often in a “ring” shape (fig 1). For the fish, there’s a certain distance that’s just “too far” outside that perimeter and not worth their energy, so obviously, you want to target your fly to land within that perimeter (i.e., the red “X” in fig.2).

- Note the Current’s Trajectory (fig. 3). You’ll need to understand the current’s speed and direction so you can use it in step 3 below. You could do this by observing the rings of the rises themselves, but they disappear quickly and can distort your perception of the flow, so that’s not very reliable. It’s better to spot something else that’s floating on the surface (such as a leaf) and visually track it for a moment. Or, throw something into the water that floats into a place that won’t disturb the fish and measure with that.

- Visualize your Casting Perimeter. Now, imagine your own “casting” perimeter somewhere ahead of the fish where it will align with the fish’s rise perimeter, and cast your fly into it (fig. 2). The red X marks the spot! Now, floow your imaginary casting perimeter and follow it down with the current as it drifts over the fish’s rise perimeter. As long as your fly lands within your casting perimeter, it’s aligned with the fish’s rise perimeter, and you’ve accurately judged the current speed, your presentation will be within the fish’s comfort zone. But in order to effectively do this, you need to have precise muscle memory of your total line length (+tippet) so you’ll know exactly where your fly will land. So make a few practice casts first somewhere away from the fish so you can accurately gauge it.

- Swing at Every Pitch! Once you think your fly is within the rise perimeter, as soon as you see ANY rise, assume it’s to your fly and set the hook! This is a game of chance. So you might lose a lot of fish at first (if you’re not used to midge fishing), but don’t worry. It will get much easier as you hone your observation and intuition, and honestly, missing fish is par for the course in midge fishing (for a variety of reasons).

You can employ this technique whether your fishing upstream, downstream, or across stream. As a general rule, I prefer either a downstream dead-drift or cross-stream dead-drift presentation for surface midges. In an straight upstream dead drift, the fish see the tippet or line first rather than the fly. This is less critical when fishing larger flies, but the diminutive size of midges exaggerates everything and greatly increases the chances that the fish will see something that just doesn’t look right. So I like to do everything I can to mitigate that.

Perimeter strike detection is my go-to for almost all of my midge fishing and has been responsible for more spectacular days on the water than I can count. If you struggle to detect strikes with midge dries or emergers, you might find this approach refreshing since it takes the pressure off to “see that god damned fly!” and focuses instead on a more eye-friendly “perimeter”.

In addition to that, I love this technique because it forces you to really get in tune with what’s going on. You have to study the trout’s cadence, identify your target, aim, execute the cast just so, synchronize with the current, and be fiercely vigilant for the strike! It’s all about observation, mindfulness, and elegance. I feel a deeper connection to the aquatic drama unfolding before me when I’m midge fishing. And isn’t that one of the reasons we adore fly fishing so much?