I recently started a new hobby: pipe smoking. And already, I can see many parallels between it and tenkara. That’s for another article, but one thing I’m particularly struck by (or perhaps reminded of) is that just like learning tenkara, fly fishing, climbing, guitar, stamp collecting, or any new endeavor, one has the option to partake of it casually, obsessively, or at any level in between which suits you. I happen to have the unfortunate foible of leaning toward the obsessive in such ventures and so before I knew it, I had spent thousands of dollars on upscale pipes from Italy, Ireland, and Scotland, various premier tobaccos, and a pile of accessories–special pipe lighters, tobacco pouches, pipe racks, cleaning tools, etc.

And while I lie on the ground, looking back up form the bottom of the rabbit hole, I try to find some comfort in telling myself that there are pipe collectors out there spending thousands on just ONE pipe, have hundreds of them, and even have whole rooms dedicated to smoking adorned with custom-built pipe displays made from exotic woods. I’ll bet they even have a custom license plate like “PIPR1” or something and a closet full of those ornate silk smoking jackets too. But then there are those who are content to fill their $3 drug-store corn-cob pipe with Half & Half and use an old rusty nail as a tamper. I suppose that lands me somewhere in between then.

But I recognized the pattern. It’s the same approach I took to learning fly fishing. I was indoctrinated early on by fly shop OGs and TU curmudgeons to believe that if one were to be successful in fly fishing, one had to learn entomology. So, as eager and naive as I was, I dove head first into it. And one book was crucially influential in my education: “Mayflies, the Angler, and the Trout” by Fred L. Arbona, Jr. (ISBN #0876912994).

To the young, aspiring Jason Klass, this book was more sacred than the Bible.

During lunch breaks at the fly shop, I’d peruse the pages religiously and diligently take notes to review that night at home. I was assigning myself homework!

During lunch breaks at the fly shop, I’d peruse the pages religiously and diligently take notes to review that night at home. I was assigning myself homework!

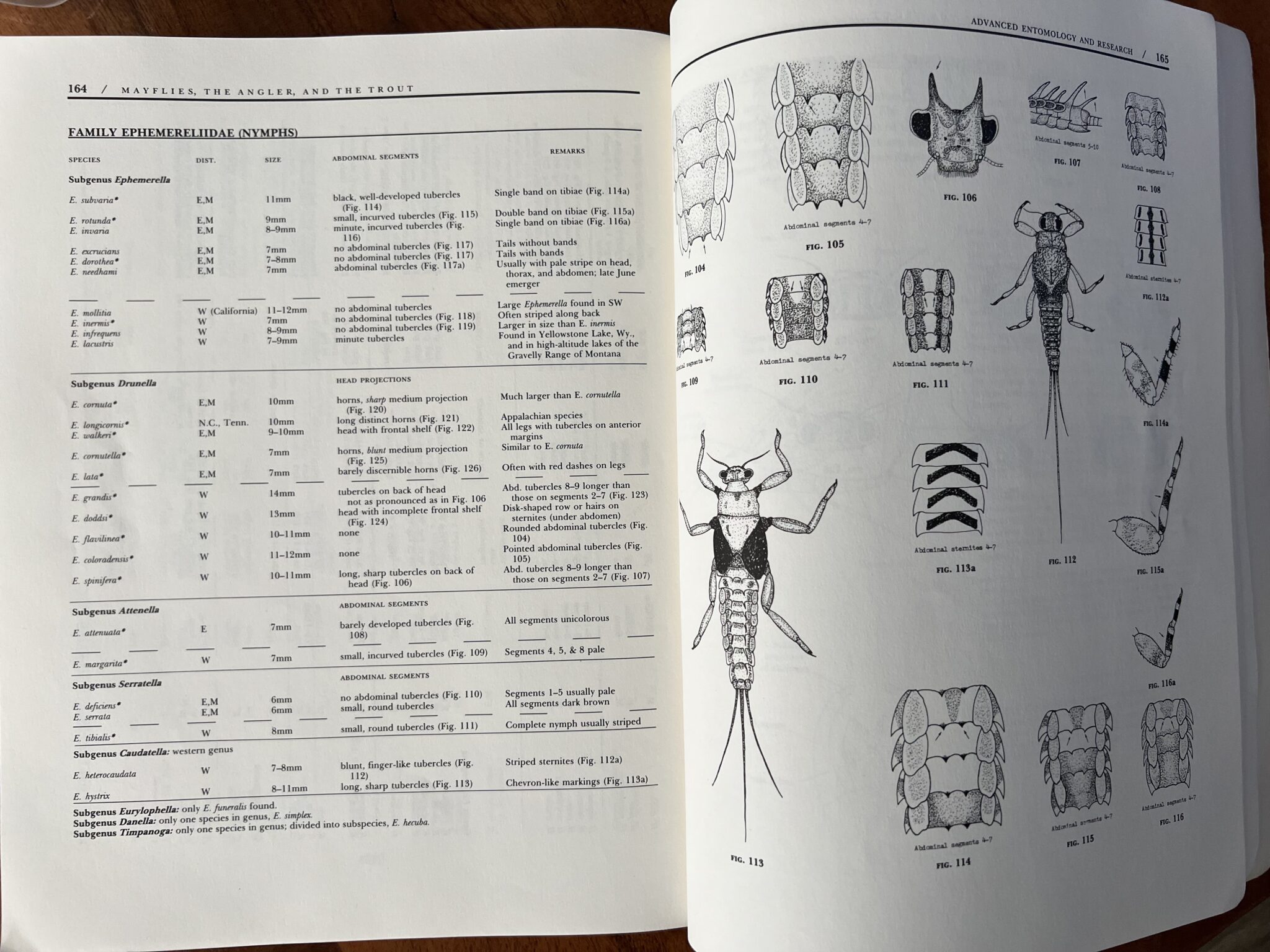

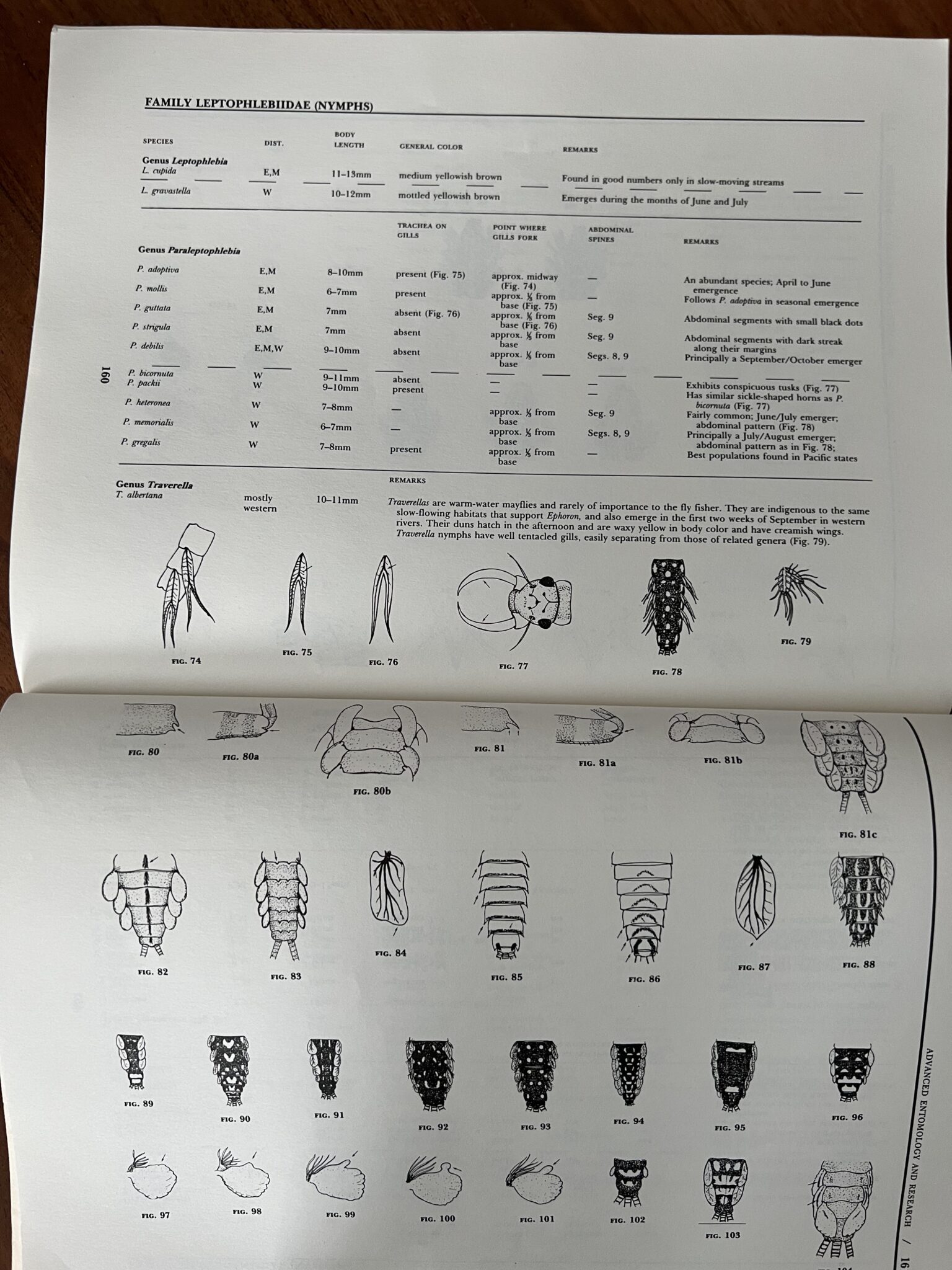

This book is extremely thorough–painstakingly detailing all the anatomical minutia of hundreds of species of mayflies. It’s complete with entomological porn centerfolds too!

While the study itself was fun, this information didn’t really prove useful on the stream. I found myself relying on my empirical observations and gut instinct as usual because that’s what I had confidence in. And it worked. So somewhere along the line, I abandoned my academic study in favor of observation and deduction and have now narrowed down my theory and approach to entomology to what works best form me while still providing a challenge and without wasting hours committing a raft of Cliff Claven entomological triva to memory.

What you Need to Know

I contend that one can gain a good, working command of aquatic entomology by simple, empirical observation to form generalities that guide the angler towards a more wholistic understanding of a particular insect culture. For example, Every year, at X time, you notice bugs that are X size, and X color. Once you observe this enough, you start getting in tune with the cadence of the stream instead of a textbook understanding and analysis. There are really only three things you need to know if you want to “match the hatch” without earning a degree (in order of importance):

1. Size

2. Shape

3. Color

In fact, one could argue that only the first two are the most important while color is the least relevant. I have my own opinions on that which is the stuff of another article. But let’s just say that armed with this simple trilogy of information, it’s sufficient to to gain an understanding of the local fishes’ quarry (at least a better one than those who don’t bother to lift up rocks). So just taking a few minutes to see if you can match what you find in your net to what you have tucked away in your fly box already gives you an advantage (and hopefully a deeper appreciation for how intricate and beautiful the underwater world really is.

What you don’t Need to Know

The differences in thoracic length between Epeorus pleuralis and Stenonmena vicarium, how many tails a baetis rhodani has, or the number of abdominal segments on a hexagenia limbata.

Dropping latin names and such minutia might impress a few cronies at the the fly shop (or, they might be rolling their eyes thinking you’re a blowhard) but does it really help you on the stream? What does that add to the crucial information of size, shape, and color? Nothing. I spent hours learning the latin names of insects; their characteristics, and subtle differences. And I can’t point to one instance on the stream where all that data actually helped me. Color, shape, and size. That is all you need to know. But of course, you need to catch them first!

How to make your own insect collection kit for under $5

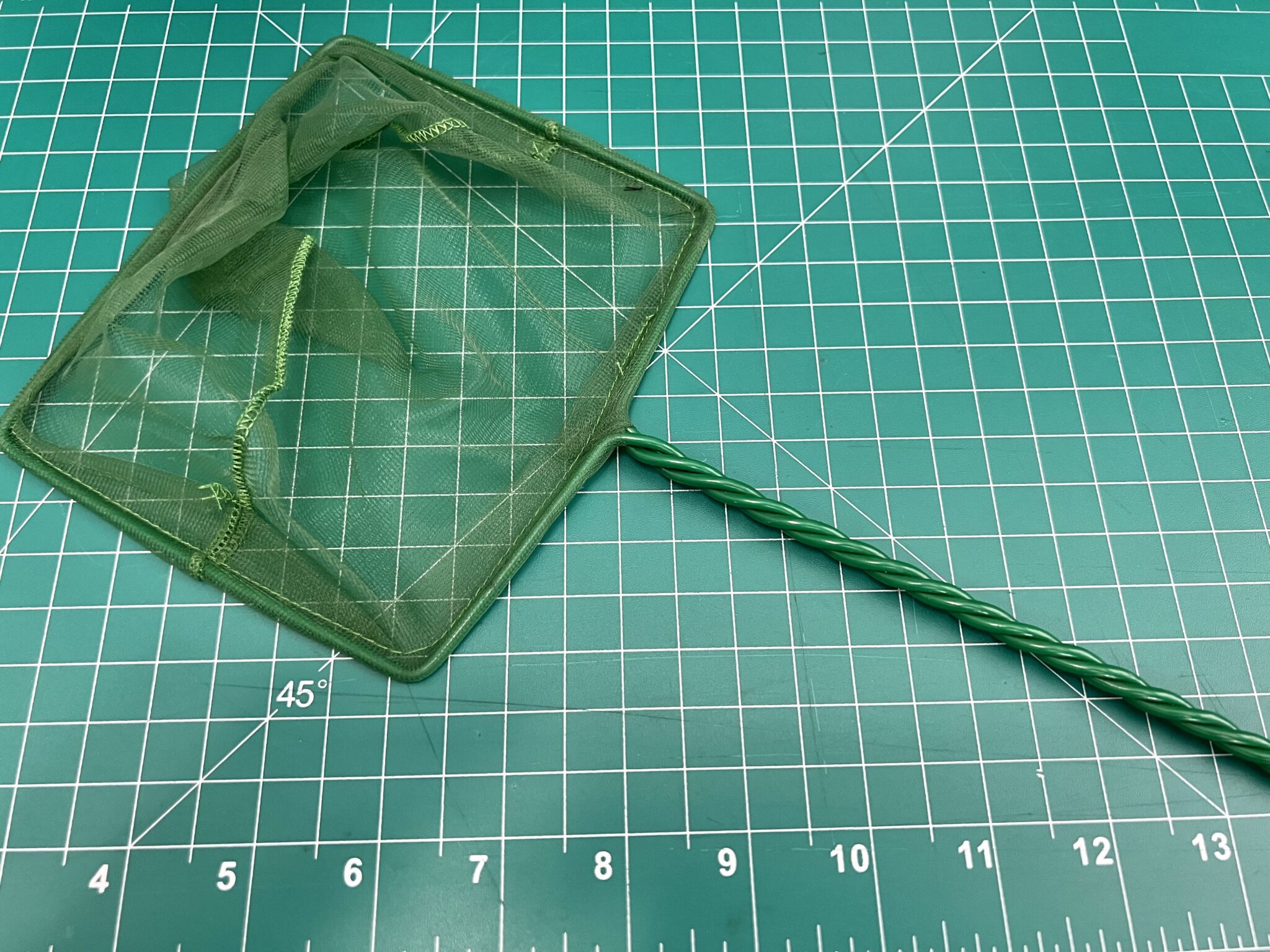

Over the years, I’ve pared my kit to nothing more than a net and a couple of viewing containers. I’m not scientifically jarring and classifying anything. I just want to take a quick sample of what’s living in the stream, get a general impression of the most prevalent shapes and sizes, maybe take a few pictures, and that’s it. So, why do I need more? Here’s a simple kit that’s more than functional for the average fly angler that you can put together with things you might already have or can buy inexpensively.

What you Need

1. A simple aquarium net with a long handle. I prefer the rectangle shape because I feel it covers more water and a longer handle to get down deeper under rocks or other structure. If you don’t have an old one laying around, you can get them cheap at your local pet store or online. I bought a pair of these for $5 on Amazon with free shipping. I didn’t want two but then figured I’d probably lose one eventually, so I might as well have a backup.

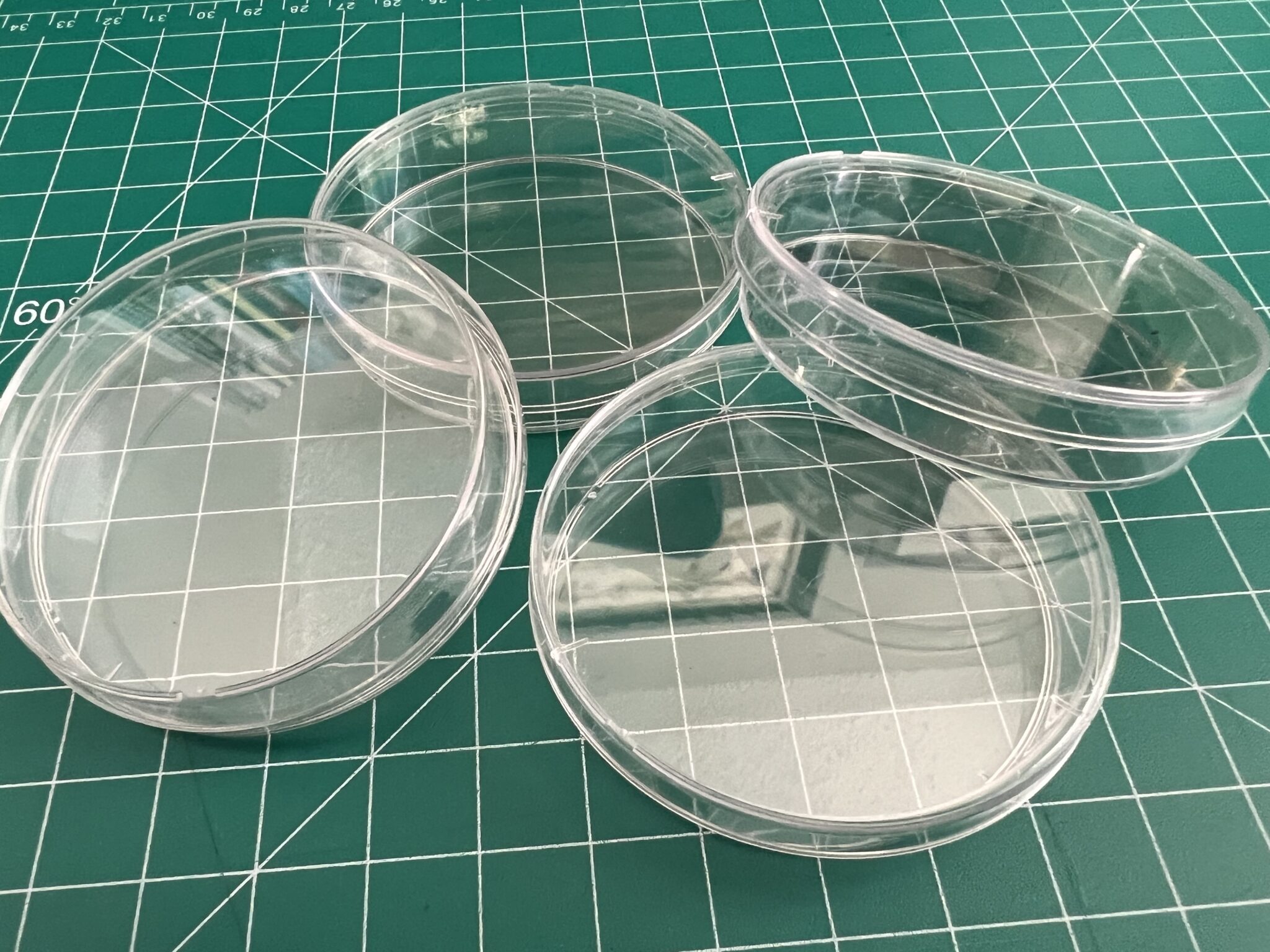

2. A viewing jar. (AKA “viewing dish”) Traditionally, this would be a Petri dish–the same ones used in pharma or medical research. And you can easily buy these online as well. I bought a pack of 10 of these on Ebay for around $10.

But I have one problem with them: they’re clear. If you think about it, out afield, you’ll need to put your jar down somewhere to view, count, or photograph your samples. A sand, stone, gravel, or leafy background isn’t good for viewing. Since most nymphs and larvae are dark colored, the ideal background would be white. So, the best solution I’ve found is actually a free one. You can easily make a great viewing jar by cutting the bottom off of a white container like these yogurt cups. Just cut around the base and leave at least a 0.5″ (12.7mm) lip. I like to use yogurt cups because they nest into each other so you can carry multiple viewing dishes without taking up additional space. Don’t worry about not having a top for it. The mayfly nymphs aren’t going to leap out of the dishto freedom a la Free Willy.

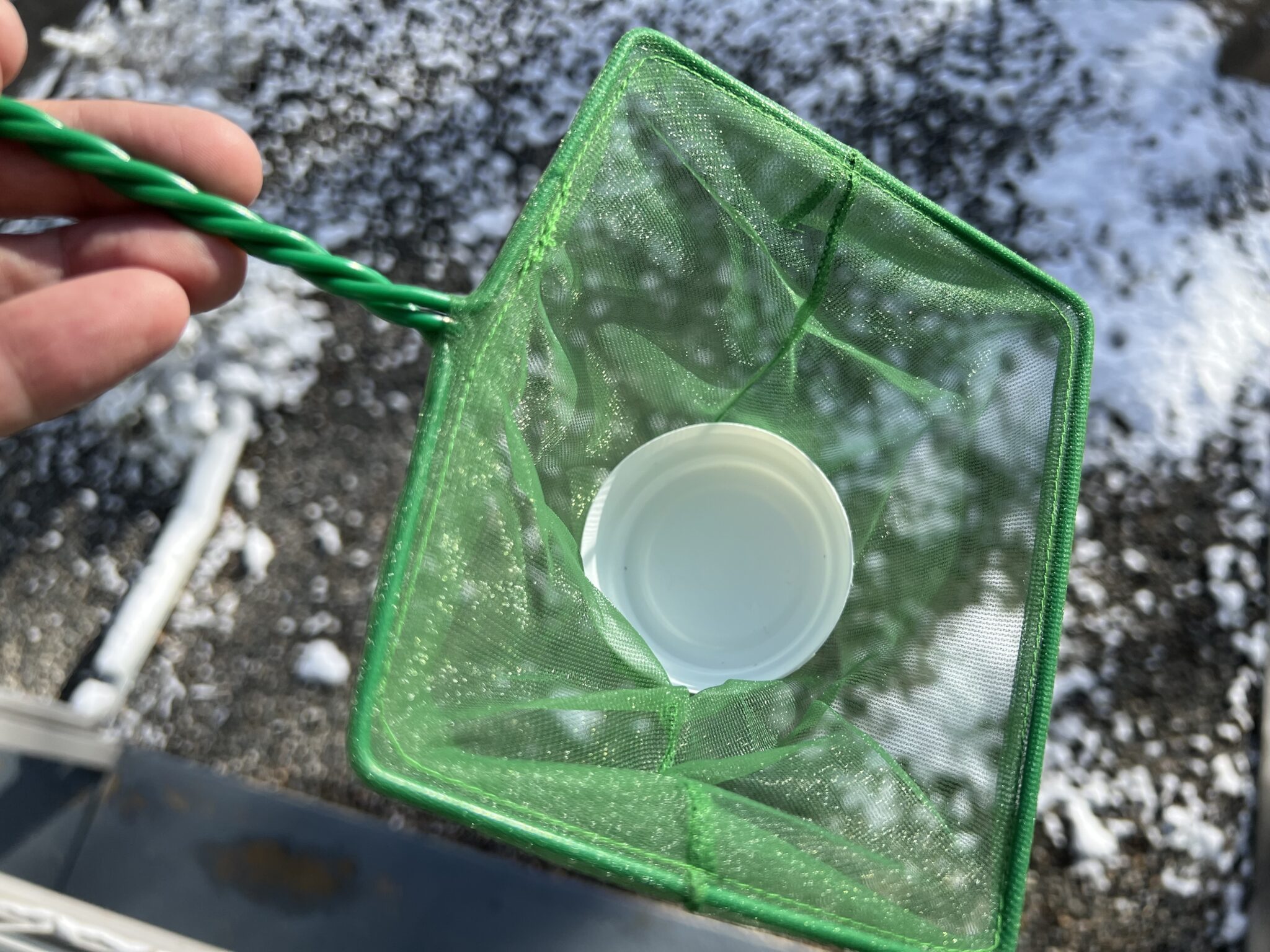

You can also up-cycle plastic lids with a lighter colors like these white ones. Any color will work but the darker colors aren’t the best. Choose white if you have them.

While these work and literally take zero time or money to construct, they’re sometimes too shallow and water can easily run out. That’s why I prefer cutting my own–I can make the lip as shallow or as deep as I want.

3. (Optional). If your phone doesn’t have one, a small magnifying glass might be helpful. And if you are interested in learning more about aquatic entomology beyond the basics, you might want to carry a small identification book or download an insect identification app on your phone such as Aqua Bugs. Caveat: just make sure the app is specific to aquatic insects. Many only identify terrestrial insects.

To store it and carry my kit, I just put the viewing dishes inside the net, cinch it closed with a rubber band, and shove it in the outside pocket of my sling. It stays out of the way but its easily accessible when needed and doesn’t get anything wet inside my pack.

My Tilley hat also comes in handy for viewing flying adults. 🙂

What you don’t need

A raft of professional-looking gear like killing jars, tweezers, stomach pumps, etc. All of that other equipment is unnecessary for most anglers’ needs.

Your entomology kit doesn’t have to look like Thomas Edison’s Laboratory to be effective. After all, you’re not a professional entomologist, you’re an amateur. Start acting like it!

Even though you might not know exactly what you’re looking at, it’s fun to catch a small glimpse into the myserteous underwater world of these intriguing creatures that keep our precious trout and trout streams streams alive.

My kit may be minimal, but it works just fine for my needs. It’s light (1.7 oz. / 48 grams), takes up no room in my pack, and inexpensive, yet does exactly what I need it to do swimmingly.

It sure beats manhandling the bugs!

Important! Please be extra cautious when collecting and viewing aquatic insects. They’re extremely delicate and populations take a long time to replenish. And as the lifeblood of our beloved watersheds, we want to make sure we leave as little impact as possible. Also, in some states, it is illegal to remove insects from the water. So be sure to check your local laws before you start bug hunting.

I am soon to be 73 and never smoked. My father died when he was 58 after 45 years of smoking. He never saw his grandkids. He never experienced their first fish, their ball games, graduations, or weddings. I really miss him and wish that he were still around. I urge you to stop smoking. It really is not worth it.

Of course supposedly any fly can catch fish….presentation is really most important. Having a little bug knowledge never hurt anyone. If anything it is one more tool to help you decide the size, shape and color of fly you will pull from your box and tie on. I’m a size and color guy myself. Shape isn’t quite as important. I’m maybe more specific on shape as it matters to soft or firm hackle.

Nice to see this article.