When your fishing partner catches the first fish of the day, the inevitable question is, “what did you catch him on?” It’s as if the fly were the ultimate “magic” factor in catching the fish. And, in fact, we all kind of place that faith in the fly … don’t we? We automatically place the burden of success on the fly. After all, it makes sense. The fly is the most immediate thing between us and the fish. So why wouldn’t it be the make-it-or-break-it factor? The truth is, there is much more to it than that.

When your fishing partner catches the first fish of the day, the inevitable question is, “what did you catch him on?” It’s as if the fly were the ultimate “magic” factor in catching the fish. And, in fact, we all kind of place that faith in the fly … don’t we? We automatically place the burden of success on the fly. After all, it makes sense. The fly is the most immediate thing between us and the fish. So why wouldn’t it be the make-it-or-break-it factor? The truth is, there is much more to it than that.

While the fly pattern is a convenient scapegoat there are so many other factors that go into catching a fish we tend to ignore that I felt it worthy of exploring at least one: temperature.

Those of us who “scratch the hatch” might think we can also ignore things like temperature, but the reality is while the pattern might not make much of a difference in many cases, the temperature does. I took an informal survey of how modern anglers approach the water and was somewhat surprised to find out how few considered water temperature and how few even owned (let alone carried) a thermometer.

As we know, trout are cold-blooded animals. Their activity and diet are affected by temperature just as ours is. You probably don’t want to eat a large, heavy meal on a sweltering summer day anymore than you’d want to eat a dainty salad on a cold winter day. Please don’t misread that analogy–I’m not saying that trout only want to eat large meals when it’s cold and small fare when it’s warm–only that, like us, temperature affects the appetites and behavior of trout.

Every animal on earth has a temperature range that’s optimal–even if they can tolerate temperatures outside of it. And it’s within this range that the angler hopes to find trout–when their metabolism and appetite are most favorable for being tempted. First, let’s look at a few numbers and then briefly interpret what they might mean to the angler.

A simple temperature guide for trout fishing

- 40°-50° Sub-optimal

- 55°-65° Optimal

- 70°-78° Sub-optimal

That’s a general rule-of-thumb that’s guided me more for freestone streams whose temperatures fluctuate as opposed to tailwaters or spring creeks (which tend to have more consistent temperatures). More precise figures could be further broken down into optimal temperatures by types of trout and char:

- Brown Trout: 60°

- Cutthroat Trout: 55°

- Brook Trout: 54°

- Rainbow Trout: 55°

So, what does knowing the temperature tell you?

Three things …

- How active the fish are. Obviously, fish are going to be more actively feeding and receptive to a fly when within their optimal temperature range. A brown trout may be more willing to chase a fly at 58° but not at 42°, so the temperature can tell you if moving the fly might produce, or whether a dead drift will be more successful. The temperature also dictates insect activity, which in turn, influences fish activity. Most species of aquatic insects require X number of days at X temperature to mature and hatch. So when the insects are active, the fish often follow suit. And a third consideration is oxygen level. Extremely warm water can be oxygen deprived, leaving the trout apathetic. Extremely cold water can have a similar affect, slowing down their metabolism. All of these will give you cues as to how active the fish will be and help you tailor your presentation to fish that might be enthusiastic or lethargic. I realize these are generalities, but to go into them in any depth is beyond the scope of this article. It’s just important to be aware that temperature affects a trout’s motivation level.

- When to fish. Just like the grandpa shushing his grandson in the boat so he doesn’t “scare the fish”, a popular myth is that the best time to fish is always early in the morning. While this is sometimes true, the exception is more the norm for me. For example, many of my local streams are in deep canyons. The water temp. drops significantly overnight and often, the best time to fish isn’t until the sun has come up over the ridge and has had time to warm up the water to a more optimal temperature. Counterintuitively, the best time to fish these streams is midday–when the early risers have called it quits, packed up their waders, and headed home thinking it’s “too late” to fish anymore. In such situations, the temperature overrides time of day.

- Where the fish are. Imagine you’re in a restaurant and they seat you right below the air conditioning vent. You’d probably ask to be moved to another table to be more comfortable, right? Trout do the same thing. While they have their preferred lies, they will move out of these to seek more comfortable temperature zones. So on hot days, the trout might move into deeper pools where the temperature is cooler. Conversely, on cold days, they might move into shallower water near the edges where the sun has warmed the water to a more optimal temperature. For this reason, it’s important to measure the temperature in various places in a stream–not just one spot.

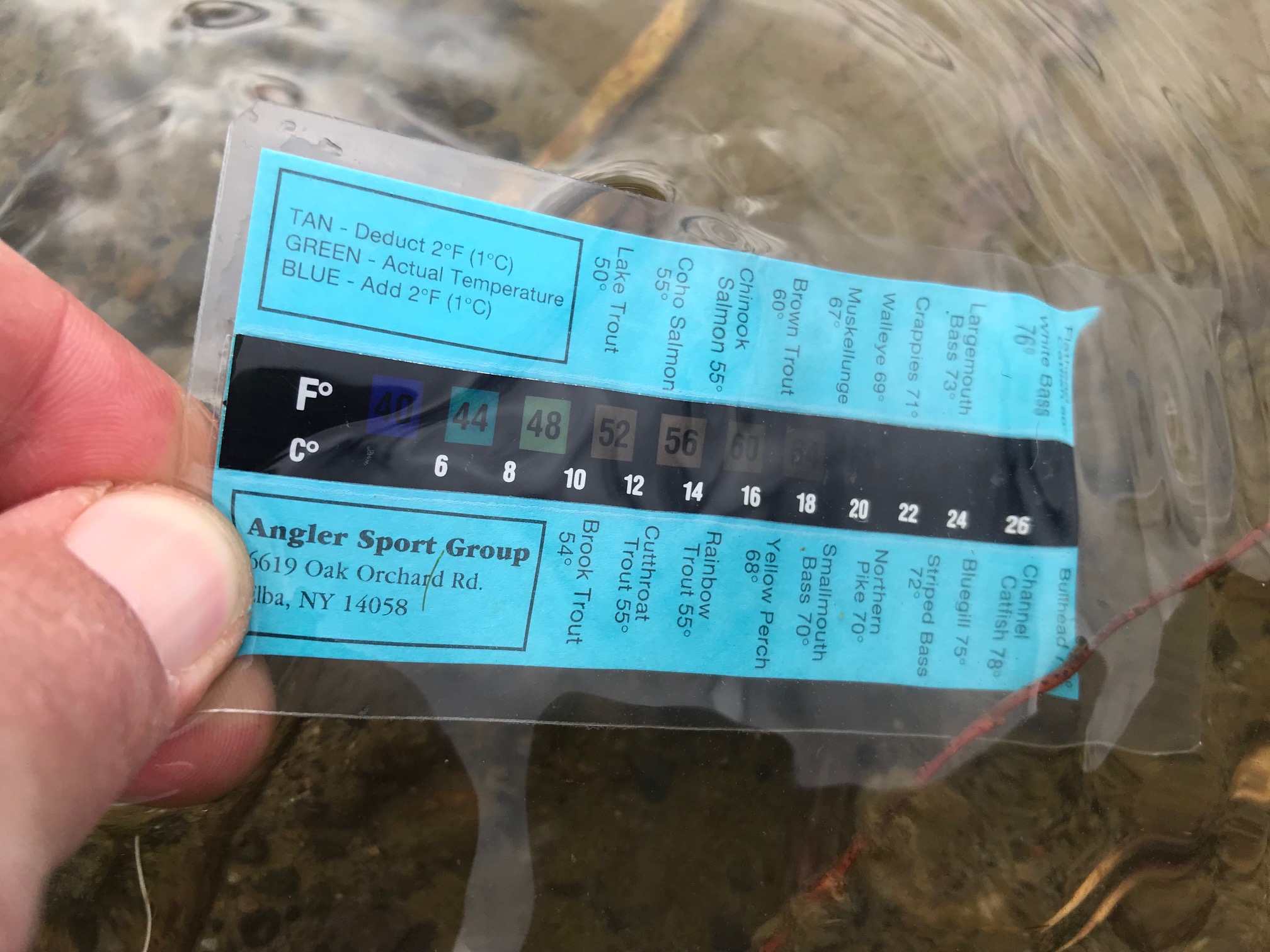

Thermometers for Fishing

There are many good thermometers available today including some high tech digital and even infrared models. Years ago, I got a free one as a promotional item from Angler’s Sport Group. It’s a flat “card” thermometer that gives a fast reading and takes up zero space in my chest pack. I’ve lived in constant fear of losing it because I’ve looked all over to find another one and can’t find one like it anywhere. So when it finally floats away one day, that’s it.

But today, I use a Fishpond Swift Current Thermometer. It’s a slow read (you have to leave it in the water for a couple of minutes), but it’s light, accurate, durable, and replaceable if I ever lose it. I’ve tied a length of paracord to it so I can drop it into hard-to-reach places such as off of bridges, beaver dams, and over ice shelves.

The number one tip I can give with regards to temperature is: Take readings at different depths, at different times of day, and in spots with and without sun. You might be surprised how much the temperature can vary in a stream. And remember, a mere couple of degrees can make all the difference!

Somewhere, there’s a biologist reading this right now and cringing at my unscientific treatment of the topic. And I welcome anyone with a formal background in the subject to chime in and educate me. But this is my empirical testament and perhaps it’s my hubris to trust anecdotal evidence over scientific textbooks.

At the very least, the next time you have a fishless day, now you’ll have one more excuse in your arsenal besides the “wrong fly” defense … “The water was too cold/warm/hot”. You’re welcome.

Jason

Great article!

As a guide I do this on my day off. Take temp readings and with my trusty Sherwin Willams paint strainer that fits perfectly over my net I follow the anglers upstream within discrete fishing distance take both samples when they move. Scientific as I can get but some with common sense.

Great tip Jason. I have carried a fishpond thermometer for I long time. Unfortunately seldom use it except when the outside temperatures get pretty warm and I get concerned about water temperature. Thanks to the information you shared I will start using it more.

Superb article. I’ve been taking readings since the 1980s. The info adds up over time to accurately describe levels of fish activity. Been using a digital thermometer for last 10 years. Can’t read underwater, but surface has sufficed. Thanks

What role does the SW painter strainer play in taking the water temperature?

Thom, I believe Chris is saying that in addition to taking the temp., he also samples insects using the paint strainer.

Great insight and a concise description on how to use it and what we need to be looking at temp wise.

Another factor to think about is the changing water temp., is it getting warmer or cooling. Wisconsin author, Jay Ford Thurston, claims they feed as the water gets warmer, even a fraction of a degree can make a difference. Then once he notices the water cooling, he finds they often turn off. He ties this into metabolism where he believes it goes up when it is warmer, again this is all within their comfort range. He also factors in cloud cover as an additional key factor, he talks a lot about light sensitivity in trout. He is a data hound, he has documented decades worth of trout fishing where he captures temps before, during and after fishing, weather, wind, clout cover, types of water they are active in, insects, etc. Note this is mainly Wisconsin trout fishing, but I feel it can be applied all over. One of his books is titled “Spring Creek Reward.” Might be worth checking out. I read it last winter and enjoyed it very much, it is full of little nuggets if info and observations.

Fishing in the winter (i.e.- with snow on the ground) has always amazed me. Yesterday I was fishing a smaller tail-water (water temp 40.5°f) from about 11am-3pm. This particular water is a brown trout fishery (in Northern Utah), with the occasional rainbow. I was happily able to catch some fish. I only saw two of the takes, but both (browns) came out of their lies to take the fly (even turning down stream both times). I have fished though winter a few seasons, and each time I find that fish (even in very cold water, down to 33°f!) are still very willing to move for food, and not just short distances. I definitely do not think of myself as an expert angler (I don’t think this has much to do with the fish moving), yet I continue to see many fish moving a lot when they are supposed to be sluggish. I’m not sure if this happens to anyone else, but I have always been a bit perplexed by it. Thank you Jason for your awesome posts!

Alex

That ASG thermometer looks an awful lot like the type you can get from any pet store that has aquarium supplies. If I remember right, they stick to the glass of the tank for continues reading. Might be worth checking out.

As I read this article I could not help but rewind images in my head of snippets from videos of Joe Humphrey and Doug Swisher.

Joe mentioned using the thermometer to indicate whether the water would hold support a trout population, indicate potential feeding activity levels or type of insect life.

Doug Swisher mentioned the time of day theory which touched on the topic of human comfort and potent prime feeding activity during the day and throughout the season’s of the calendar year, as good starting points for wisely using one’s fishing time.

Of course your article mentioned factors which may alter it somewhat.

Great write up Jason! For a couple of years now I have been testing Phil Rabideau’s ideas on Color Technology, of which water temperature is a key component, affecting both the size and brightness of the lure or lures required to get the best results. H2o color is also equally important as trout are mainly visual predators, and a fly attracts them better if there is a high degree of contrast (Think Light on Dark and Dark on Light between the fly and the fish’s viewing background, and on the lure itself as wel.) so the fish can more easily see the fly. Cold water requires the biggest and brightest of lures. Optimum water temps require a reduction in both size and brightness. And warm waters require smaller and duller lures still to be used.

Match-the-hatch type anglers go to great lengths to make their flies look exactly like what the fish are feeding on, which can actually be counter productive. Prey species are colored and camouflaged to insure the survival of the species. As anglers, we do not want our flies to survive. Phil’s book, “The Master Angler – Using color technology to catch more fish” has almost nothing to do with fly fishing, and yet using his color technology has helped me to catch fish at a ratio of 5 to 1 on a number of occasions compared to other anglers who were fishing the same waters at the same times, and with considerably greater casting reach than my fixed line tackle has. Here is a link for anyone interested in his book: https://www.hancockhouse.com/collections/all-titles/products/master-angler

Hi Karl, as always, great points and insights. One question … the “light on dark and dark on light” maxim. I’ve always fished the opposite. In muddy or stained water, I’ve always fished darker flies and in clear water with a lightly colored substrate, I fish lighter flies. This is an old mantra I carried over from bass fishing into my trout fishing and it seems to work. The idea is based partly on what you say–namely that a black fly would contrast better in off-color water. But then it also seems to contradict itself by using light colored flies in clear water. So, it seems that we both have empirical evidence to support contradictory maxims. And thoughts on this? Maybe the difference could be in the style of fly. For example, if you’re fishing larger flies like streamers, then the predatory instinct kicks in and your color theory applies whereas if you’re fishing smaller flies that more closely resemble drifting insects, mine does. It’s an interesting question. Curious to hear your ideas on it.

Hi Jason, I do not believe there is any simple answer to your question because it involves so very many different complicated conditions. First of all, water comes in a multitude of shades of 3 basic colors, i.e. blue for clear waters, green/yellow for waters with algae bloom conditions, and brown/red for mud stained turbid colored waters, all of which can be either flowing or still waters. The color will be the lightest near the surface and get progressively darker as the fishing level gets deeper until everything turns black, which varies for each color used in a lure, respectively – with red being the first to go, followed by orange, yellow, green, blue, and indigo in that order, which all turn black in their turn eventually.

At Tenkara fishing depths this would not seem to be a valid concern except for the fact that the color shift phenomenon applies to linear distances as well as to depth. And added to that is the fact that there has to be light of the color you are seeing present for us or the fish to see that color on the lure which will also change with distance and depth. The mistake most anglers make is in assuming that fish see things in the water the same way as we see them in the air, which is definitely not the case. It gets much darker in the water much quicker. The light loss in clear water is 22% in the first 1/2 inch, 45% in the first 3 feet, and 78% in the first 33 feet.

Blue Water Hi-Vis Colors: Silver and gold plate, white, blue, Fluorescent green and chartreuse with FL-red, Fl-pink or Fl-orange used as decorations will provide the highest visibility in clear water.

Green Water Hi-Vis Colors: Silver, luminescent white, Fl-chartreuse, Fl-red, Fl-pink and Fl-orange decorations show up the best for fish in green colored water.

Turbid Water Hi-Vis Colors: Gold, black and Fl-chartreuse are all that’s needed for red/brown stained waters, and you are right black provides high contrast in all water colors and especially against the sky. The Fl-colors require light of a shorter wave length to Light-Up to their fullest. And the color the fish see will not necessarily be the same color we see in normal daylight. An in addition to that, the FL-colors remain bright far beyond the distance where regular colors begin shifting to gray and begin to turn black.

Investing in a Black Light will allow you to see what colors the FL-Colors really are and determine if you have been fishing with flies that are, in fact, tied with FL-materials you had no way of knowing about. Also, many materials advertised as being FL- do not necessarily fluoresce. So Jason, instead of answering your questions, I fear we have opened a can of worms on a whole lot of other questions….Karl.

WOW Karl! You and I seriously need to sit down and have coffee some time. It would be a 21-hour conversation and we will only have covered the socio-economic history of the degrees of hook point angles throughout the Asian subcontinent before we even get on to the next topic of an in-depth debate on tensile strengths of silk cordage for eyeless hooks based on the strand count and to what degree various dying techniques affect its strength. For most people, “minutia” is a negative term. But for people like you and me, it’s a passion. And I have always appreciated your passion for minutia. Really, let’s at least have a phone call or FaceTime chat. I would love to open a can of worms with you!

Hi Jason. Its raining here and we can’t do much outside, so I have been thinking about your white fly technique used on streams with light colored bottom structure. And I have no doubt that the aquatic insects living in such streams would take on a light body coloration to better blend in with their surroundings to protect them from predators. But I do not think the light coloration would necessarily make emerging insects or flies tied for them any more visible to the fish, and here’s why: Counter-shading.

Almost all fish use counter-shading in their body coloration schemes to protect them from predators, with white on their undersides so their bellies blend in with the sky above, silvery on their sides to reflect the color of the water and other backgrounds predators will see them against, and they are colored darker on their backs to blend in with the darker water and bottom colors seen by predators looking down on the water from above, so a white fly would not necessarily be more visible to predatory fish. Against the sky, a black fly would provide the greatest contrast – day or night.

Black and white are not true colors. Black is the absence of light, meaning black objects do not reflect any color of light shined on them. White light is made up of all the colors of the spectrum, so white will reflect any color of light shined on it to some degree. Gray is a combination of black and white, so it will reflect gray toned light in many slightly different colors of a reduced intensity.

Fluorescent colors are a double-edged sword in that they need to be used very cautiously. Fish have no eyelids or cornea, so the only way they can regulate the light entering their eyes is to find shaded areas or to put a deeper distance of water between their eyes and the sun. If more than 30% of a fly’s surface area is made up of a FL-color, it will over load the cones in the fish’s eyes and they will back away from it, so you do not want a whole FL-colored fly. And even Hot Spots have to be used with great caution. For flies cast upstream and drifted down to the fish, the Hot Spot should be located near the front of the fly. In lakes, where the fish usually overtake a fly from behind, the Hot Spot should be located at the back or behind the fly. Some anglers have tried to cover all their bases by putting Hot Spots at both ends of the fly, but that only serves to confuse and discourage the fish from taking a fly so tied.

Like us, fish eyes have both Rod and Cone vision cells. Young trout also have UV-Cone cells, as well. But as the fish mature those cells are eventually lost and their function is taken over by the regular rod and cone cells. Rod cells are highly light sensitive but can only see black, white and shades of gray, with very little detail. The cone cells are for color vision and provide much more detailed vision that the brighter sunlight makes possible to see. But compared to human vision trout vision resolving power is about 14 times weaker than our vision. Trout are nearsighted and they can see small objects and minute motion unbelievably well, but the overall vision quality of the picture their brain sees is pretty crude, which explains a lot about why our crude representations of the food forms they eat work so well.

Your flat thermometer looks homemade using an aquarium thermometer then laminated.

The company that made them probably did just that. They used to give them out for free. When I worked at the Orvis dealer in NY, we had a stack of them on the counter and anyone could take one. The thing is though, most aquarium themometers don’t have the right range fore trout fishing–they don’t go low enough.