Today, I’m excited to publish the first ever guest post on Tenkara Talk! For years, I’ve resisted the idea, but reconsidered after being sent this very interesting article by Isaac Tait of Fallfish Tenkara, AKA, “Aki Sakana” or “Fallfish Demon”. Isaac has a unique perspective on tenkara as an American living in Japan who explores the country’s streams and going on adventures with Japanese tenkara veterans. Plus, with the holidays right around the corner, the theme seemed right. I hope you enjoy it! -Jason Klass

Rain is falling from the cold grey November sky. The pitter patter of the drizzle is only interrupted by the swoosh of passing bicycles and salarymen rushing home to warm homes and hot food. The Namerigawa River meanders peacefully through the ancient village that was once the capital of Japan. I stop to admire the black waters that shimmer as a million tiny droplets momentarily disturb the placid mirror-like surface. I don’t see any fish, though it is supposedly prime habitat for はや (Haya), aka Japanese Dace and はぜ (Haze), aka Goby. I press on and in short order I arrive at the home of Toshiaki Kado.

Kado-san and I have been Tenkara fly fishing together for two years now, and even though he is 36 years my senior I consider him a very good friend. Our friendship has been forged by fishless rivers, swarms of hornets, harrowing 5th class ropeless “rock” climbs a hundred feet above roaring waterfalls, torrential rains, landslides, countless kilometers of backcountry tracks that some would consider trails, and of course fish – thousands of them, Iwana mostly with a smattering of Amago and Yamame.

One of my favorite stories I like to tell about him took place in the Fall of my first Tenkara season in Japan. Myself, Kado-san, and Wan-san (a mutual friend) were hiking into a remote keiryu valley near Mount Asahi in Yamagata Prefecture. The trail, which was more of a seldom-travelled animal path cut a narrow ribbon up a steep hillside covered in bamboo and fallen trees. Suddenly, the hillside gave way and Wan-san was carried away in a small avalanche of mud. Thankfully he came to a stop quickly, but on the edge of a steep precipice. His feet were mired hopelessly in the mud and he couldn’t move. Kado-san and I stripped off our packs and created a human ladder – Kado-san hung from a sturdy tree with one hand and I hung from his other hand. With my free hand I was barely able to reach Wan-san. I grabbed his pack and pulled with all my might but he would not budge. I nearly gave myself a hernia pulling him but to no avail. Suddenly, we were both sliding up through the mire up the slick near vertical hillside. I turned and looked in amazement to see Kado-san lifting both of us with one arm!

From the first day I held a Tenkara rod in my hand until now, I have been fascinated with this sport. Every aspect of Tenkara intrigues me: from techniques, to the equipment, and of course the time spent in the places where the rivers are. When I moved to the Land of the Rising Sun, which is the birthplace of Tenkara, I began to explore the history of Tenkara and how it shapes and affects how we think of the sport today.

Through this interest in the history I inevitably came across the Shoku-ryō-sha (職漁者). These men fished the keiryu of Japan for a living during the summer and hunted bear during the spring; the rest of the year they survived off of the bounty of their labors. The oldest records of shoku-ryō-sha date back to 1878 from a man named Shinaemon Toyama. One thing that sets the shoku-ryō-sha apart is their ability to make Tenkara as simple as possible without sacrificing effectiveness.

For example, Toyama-san fished with cotton clothing dyed with persimmon powder. This powder dye lent the clothing a natural durable water repellent finish. They also fished with fishing line made from horsehair, and tied their kebari by hand using almost no tools – and despite the lack of technology, they caught upwards of 200 fish a day! Probably the most famous name in the shoku-ryō-sha community was Bunpei Sonehara. For me, one of the more fascinating aspects of Sonehara-san were his kebari. He used large Black Bream (a salt water fish) hooks (equivalent to #10-#12 size now a days) and chicken feathers for hackle. Dr. Ishigaki speculates that the larger sized hooks helped catch bigger fish as shoku-ryō-sha weren’t terribly interested in catching fish that were too small to sell. It was all about efficiency.

Unfortunately, due to the proliferation of dams throughout Japan, the fish stocks have nosedived and with the fish the shoku-ryō-sha have also disappeared. The last shoku-ryō-sha lived in the ultra-remote Shimominochi District of Nagano Prefecture. His name was Shigeo Yamada and he passed away a few decades ago from a heart attack on a bear hunt. This past season I spent a few days with his son in their family minshuku (a traditional Japanese inn). Next season I hope to return and spend a few days fishing with Yamada-san and learning how to make soba.

Back at Kado-san’s home on the banks of a tributary of the Namerigawa, over a bottle of wine, Kado-san and I discuss the shoku-ryō-sha and their affinity for the simple and effective. Kado-san has been an avid Tenkara angler for nearly four decades and through his journey he has perfected his kebari which are strikingly similar to Bunpei Soneharas’. I can attest to their effectiveness too, as the native and wild Iwana absolutely love them.

He uses Red Snapper (a salt water fish) hooks – both the eyeless and eyed varieties in gold and silver. The silver hooks are offset, similar to Adam-san’s “wrong kebari”.

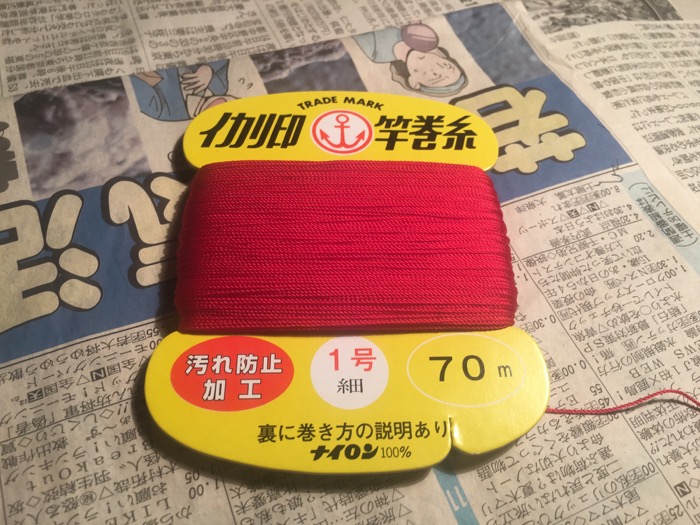

The thread, of which he prefers red and green, comes from a nearby sewing store.

The hackle are white chicken feathers that he gets for free from a friend who only uses the small feathers from the bundle.

The flies which are red, green, and white with a little silver or gold tinsel remind me of a Christmas tree. Despite the fact that these Christmas tree kebari look nothing like any bug in Japan, they catch a lot of fish and their simplicity harkens back to a similar time when the river’s inhabitants were more plentiful than people.

A Christmas Kebari in the making …

Isaac & Jason. Thanks for this interesting essay. Friendship, adventure, Tenkara history, and cool kebari.

excellent wednesday morning read and photos . . . still in bed at -10F

Love me some Japanese Tenkara.

Thanks for guest posting.

Thanks for the post Issac and Jason. Nice to get a local view and to see some of the simplicity that still rules in some areas. Rob

Isaac – I lived in Japan circa 1981 working at the Navy Base Yokosuka and had a Japanese friend Toshiaki Kado who owned a surf shop in Akiya Beach. I have been trying to reach out to him and your picture looks exactly like him. Can you perhaps give me his contact information?

Thanks,

Paul

paulgil@cox.net